I’ve spent the last three years of my career as a doctor for the Amish. It is frontier medicine. I can regale you with stories of mangled hands immersed in cans of kerosene, arms and legs impaled with any number of small metal objects, injuries wrought by farm animals and table saws, of medical problems in states of extremis seldom seen and treated in outpatient clinics, of croupy toddlers finding relief from my breathing treatments at 2am. I splint, cast, stitch, nebulize, hydrate, I.V. medicate, ingrown toenail extricate, and eye foreign body eliminate, all comers aged 1 day to 99 years. And I treat diabetes and high blood pressure, too. These are the joys of Family Medicine.

A day in the life of a doctor for the Amish.

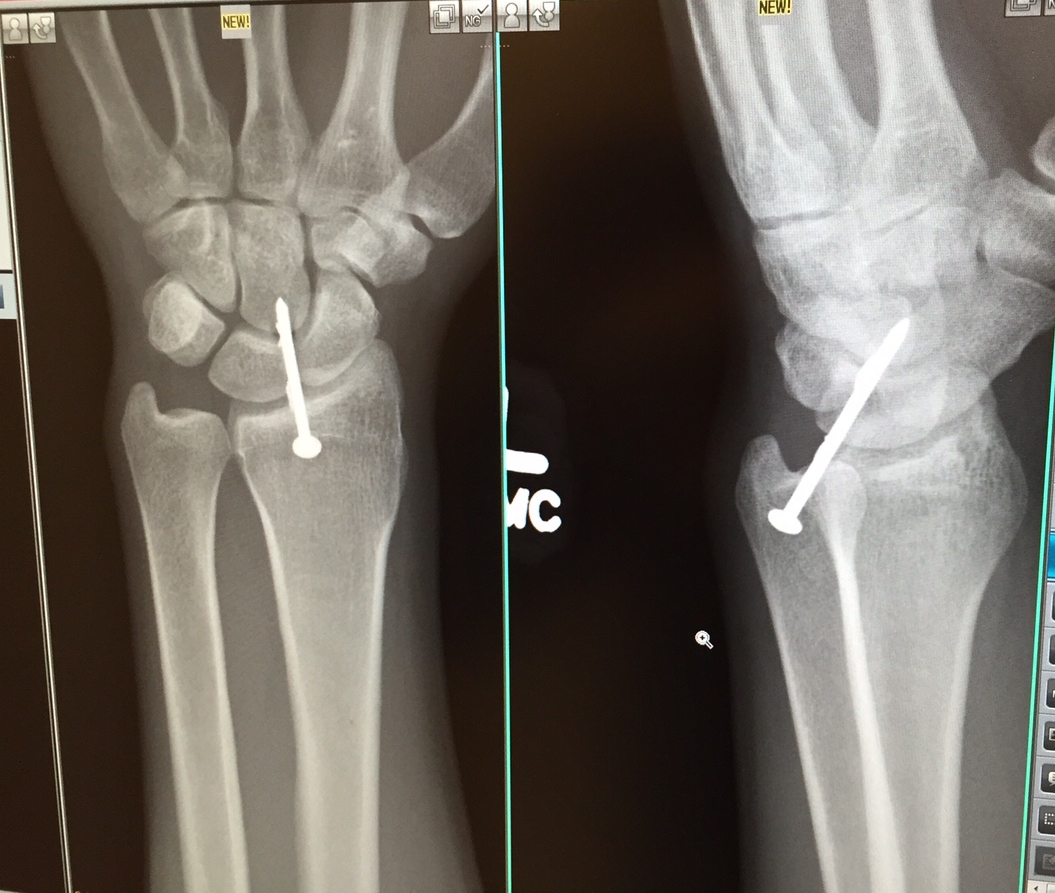

I will launch CovenantMD, my new solo Direct Primary Care practice, in the next few months. But my current office is a multi-provider practice that was begun eleven years ago by the Plain Community (Amish and Mennonite) of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania as a place for them to enjoy self-pay, low cost, yet mainstream medical care. It was developed as an alternative to the insurance-taking clinics that make a habit of fleecing patients that pay cash (the Amish, for religious reasons, do not carry health insurance, and are exempt from the individual mandate of Obamacare). Here, you will recognize the trappings of a mainstream medical clinic. But there will also be differences: the tie-ups for horses and buggies in our parking lot, the a la carte price list for our services, the paper charts (the Plain People distrust technology), the Mennonite staff, the procedure room wall lined with mechanical tools more at home on a mechanic’s bench (these enable us to remove those metal objects I spoke of, and pictured, above).

And we save our patients a lot of money. We save them emergency room visits. We offer low-cost medications through our in-house pharmacy. We offer low prices on local MRI’s and CAT scans. We have lower cost arrangements with specialists in our areas, and some local hospitals have begun bundled price plans so the Amish can know immediately how much an appendectomy (for instance) will cost.

But in other ways, I have struggled as a doctor for the Amish. They continue to display a lack of trust in Western medicine (by “Western,” I mean what is considered mainstream medicine in America). They seem to have no doubt that we are what they need for acute injuries, but when it comes to routine medical care, and especially preventive medical care, it is a tough sell. Why is that? I think it boils down to the fact that the Amish have these perceptions:

Western medicine is hubristic (i.e. It thinks it has the corner on what is broken in the body, and how to fix it).

Western medicine is expensive.

Western medicine is “unnatural.” (In other words, doctors employ man-made, synthetic substances over herbals and supplements that occur in nature.)

I sense that I succeed as a doctor for the Amish only to the extent that I come to terms with these three perceptions. And that journey has, without doubt, made me a better physician. So here are the lessons I’ve learned from the Amish:

Lesson #1: I must lay aside my agenda in order to earn the trust of my patients.

I was trained at the ivory tower of Western medicine: the inner-city academic medical center. When I arrived at my current office, I came ready to enlighten the Amish of the virtues of Western medicine. But I quickly discovered that mainstream medical doctors don’t enjoy the same prestige with the Amish as they do in the “English” (non-Amish) world. In their eyes, they have a large menu of medical professionals to choose from: midwives, chiropractors, herbalists, nurse practitioners, Aunt Linda (or any ubiquitous self-appointed family medical expert), and medical doctors. And those that are more prone to use what the Amish view as “natural medicines” will be the preferred experts. So you can see that we doctors have a disadvantage right out of the gate.

Let me give an example of the tension between Western medicine and what the Amish would regard as more natural diagnosis and treatment. My current practice is Lyme Disease central. For the last 3 years, from late-May to early July, we see 3 to 5 cases per day of erythema migrans, the early stage of Lyme disease (which makes me chuckle at this article from Lancaster Online). Through the rest of the year we see several cases of secondary Lyme disease (usually acute arthritis). Lyme is a true epidemic in Lancaster County. But Lyme also gets an inordinate share of the blame for sundry nonspecific medical symptoms, like fatigue, and headache, and nausea. Western doctors have tests that say “Lyme disease” or “not Lyme disease” in pretty clear language. But there are other practitioners that use tests, like electrodes on the finger, or saliva tests, or blood tests not approved by the CDC, that say “Lyme disease” far too readily. And then these practitioners readily prescribe expensive several-month regimens of “natural” medicines.

When I started at my current office, I would give my patient taking “naturals” for “Lyme disease” a full broadside. “You are being taken advantage of!” I would tell them, or “I don’t believe any of your symptoms have anything to do with Lyme. Why don’t we do the REAL test and see if you actually have it?” And that was where I lost them. More times than not, these patients did not “see the light” and forswear folk medicine in favor of the proven knowledge and effectiveness of Western medicine. They just didn’t come back to see me.

The lesson I learned was that I needed to listen. I needed to listen to their priorities. I had to try to weave Western medicine into the complex and sometimes baffling tapestry of their belief system. And you know what? I had to acknowledge that some of the remedies they used, that I would disdain as “folk,” did make them feel better. I had to acknowledge that some mainstream medical treatments, from antibiotics to anti-depressants, had every bit the dependence on the placebo effect that “natural” remedies had. I had to acknowledge the mystery that still shrouds the diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease. I learned that for any remedy I might suggest, for whatever ailed them, I would need my patient's “buy-in” and commitment in order for it to work. And let me dare say (at the risk of offending my doctor colleagues) -- sometimes I made my desire to avoid over-prescription of antibiotics secondary to meeting my patients’ belief that “an antibiotic” was the simple thing they needed to kick their viral illness. And it did always seem to kick it.

Lesson #2: Informed decision making between doctor and patient must necessarily include a consideration of cost.

In 2015, patients are insulated from the true cost of medical care. That’s because a third party (an insurance company, your employer, or the government), is footing the bill. But doctors are also insulated from the true cost of care. We doctors generally have no idea how much a test or drug actually costs your insurance company, or even worse, how much it costs you. This is one of the problems that contributes to the dysfunction in our healthcare system -- a lack of price transparency.

So it was a shock to my system to step into this office three years ago, into the world of self-pay medicine. The typical drugs I used to treat migraine headaches and diabetes, for instance, were just not options for the Amish because they were very expensive. I had to adjust my practice in order to offer the most cost-effective treatment. If I didn’t, I found that no matter how convincing I thought I sounded when advocating for a particular test or treatment, my Amish patients were prone to reject it if it was too expensive.

The beauty of Lancaster County. The view from my office.

I’ve discovered that engaging the local hospitals, radiology centers, and laboratories in order to get cash discounts on things like MRI’s, or gall bladder removals, or orthopedics referrals, didn’t just save the Amish money. Lower prices removed barriers to care. They made it more likely that the Amish would see a Western doctor.

These days, the “English” (non-Amish), insurance-taking world is looking more like the world of self-pay I’ve grown so accustomed to over the last three years. As deductibles get higher, and employers cover less of the cost of insurance, people are seeking value in healthcare. But it’s one thing to know you must seek value. It’s yet another thing to find it. I can show my Amish patients one book that includes all our prices for labs, tests, and surgeries at local hospitals. But can we do that in the “English” world? More often than not, you can’t shop around for price. Again, we need to advocate for price transparency.

Lesson #3: I need to invest time in helping my patients make informed decisions, even if they don’t ultimately follow my recommendations.

The Amish don’t take anything for granted, including "medical expertise." They want to know reasons, they want to know cost, and they want to know options. I can’t just say, for instance, “Your child needs tetanus immune globulin for this cut, because he’s not immunized,” and hand it off to the nurse. That shot costs $380! So I quickly found that it was necessary to carefully explain the logic behind giving this shot, a clear explanation of cost, and the risks and benefits of giving it or not giving it.

A young Mennonite couple brings in their first-born, 6-month-old son for a well-child visit. At the end of the visit we begin a conversation about immunizations. In the “English” world, I never had conversations like this. My patients took it for granted, for better or for worse, that immunizations were the “right thing.” But for this couple, their decision today, and in the future, has many things in play, including the cost of the shots, whether to accept free immunizations provided by the state, which shots protect against diseases that are sexually transmitted (they may object to these shots), which shots are required by the state of Pennsylvania for entry into school, the risk of autism from the MMR shot (which I do not think exists, but is a real concern for my patients), etc. My counseling session with each family usually involves a diagram of some kind, a gentle statement that I as a physician endorse the immunization schedule recommended by the CDC, but that I will respect whatever the parents decide once they are given the facts. I give them time to ask questions and time to sit and think. This is a time-consuming conversation. In one regard, I lose every time — I have yet to see one family accept the oral Rotavirus vaccination, and still only about 5-10% of families administer the pneumococcal (pneumonia shot) to their children. But in another sense, I win every time, as I think every couple leaves feeling that they’ve made an informed decision for their child.

Lesson #4: Patient trust is best earned in the context of a long-term relationship.

This is one of the primary reasons why medical students go into Family Medicine. They look forward to that long-term, trusting relationship with their patients. In the "English" world, such a relationship is relatively easy to build, as Western doctors enjoy prestige and are generally regarded as having the corner on medical knowledge. But to the Amish, medical doctors are on par with a host of other practitioners. So it was with my Amish patients that I experienced the real work of building a doctor-patient relationship. Such a relationship is like any other — ideally, it is painstakingly won over a long time. A doctor and patient must grow together in knowledge and humility (because the more we know, the more we realize we don’t know), in success, in failure, in pain, in sorrow, and in joy.

Lesson #5: A doctor with Amish patients should strongly consider training in Integrative Medicine or Functional Medicine.

As I’ve mentioned, the Amish will always prefer “the natural route” first. Were I to stay in my current office (or if I am so blessed as to gain Amish patients in my new practice), I would seriously consider training in one of these modalities. Scientific evidence is the sine qua non of Western medicine. If science doesn’t demonstrate a treatment’s effectiveness, then we risk harm to a patient if we subject him or her to that treatment. (There is much controversy in the medical community as to what constitutes “good evidence,” but that might be the subject of another post.) The challenge for a doctor is choosing alternative treatments that have a good base of evidence demonstrating effectiveness. Those treatments are out there, and they are many. It is hard to find such courses of learning in mainstream medical schools and Family Practice residencies. But I sense that is changing.

I am excited to begin CovenantMD. I am excited to apply the lessons I’ve learned in treating the Amish to my new patient population. I hope the Amish find value in the Direct Primary Care model (I’m not yet sure about this), because I think there is much I can still learn from them.

Patrick Rohal, M.D. is a family doctor. He will soon be opening CovenantMD, a direct primary care practice, in Lancaster, PA. He lives in Landisville with this wife, Lynn, and three kids.